We’re excited to present our first Tapestry Supper from the African continent! Tahera and Arif Karim are Bay Area transplants of Tanzanian and Kenyan descent. Their lunch on Sunday, September 17 features a menu of family recipes that hold special memories for them. This meal benefits Developments In Literacy (DIL) which educates and empowers underprivileged students, especially girls, by offering quality education opportunities and provides professional development to teachers across Pakistan.

Read on for their story or head here to check out the menu and purchase tickets.

Where did you grow up?

Arif (AK): I grew up in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. It was the largest city in Tanzania but because of the country’s state of development it felt like a small city at the time. My family and family friends all pretty much lived in the city center and everyone just walked to the places they needed to get to. You always ran into people you knew as you walked from place to place, errand to errand. As a result there was a strong sense of safety during the day. I remember walking on my own to and from school and Sunday school when I was probably five or six, and that was normal. I often played in a big sand lot in front of the apartment we lived in, with the rest of the children from the building. There were ditches near my primary school where I caught frogs for fun. There was a lot of freedom to roam and explore during my play time, but I didn’t have a lot of it, because of school, after-school ‘tuition’ and then religion school until about 8 pm. It was a busy schedule even as young as I was.

Tahera (TK): My parents shared a similar background to Arif and his parents, having come from the same community but different regions. My dad came from a small town in the foothills of Kilimanjaro called Moshi and my mum grew up in Nairobi, Kenya. My dad was a feisty adventurer, who was shipped out to live with his uncle in Iran after having been too unruly for little Moshi. He didn’t stay put very long before deciding to basically run away and hitchhiked his way to Germany and then to the UK. At some point, he decided he needed a wife from the homeland and was introduced to my mum, whose dream was to end up in London somehow and here was her opportunity! I was born and raised in the UK (London) and moved to the Bay Area because Arif promised me a promising life in the promised land! Like mother like daughter!

What were the circumstances that brought you here?

AK: My family landed in New York City when I was seven years old, where we had family friends to stay with until we found our bearings. As my dad tells it, we moved because permanent housing was hard to get in Dar because the country was socialist at the time and there was always a housing shortage due to the interference of government officials (i.e., residents had to move when the government deemed another family more “worthy” through connections, bribery, etc). The other more apocryphal reason my parents offered was because they wanted a better quality of education for my brother and I, but that was likely a way to guilt us more than anything else!

How did it feel to leave your home country and what were your hopes for life in America?

AK: Since my parents had been to the US prior to our relocation, they spoke of how great and “modern” it was. For one thing, there were taps that brought cold and hot water into your house and showers instead of heating cold water, pouring it into a big bucket and using a cup to manually rinse yourself off, which was how we bathed in Dar at the time. My dad promised there were huge buildings with 100 floors (the tallest building in Dar probably had 10 floors or so). All the roads were paved whereas we had a mix of paved and dirt roads. We would have a TV there too. I was excited to go because we were going to have a much better life as my dad promised!

What were the early years of American life like? Was it easy to adjust?

AK: The first few years were tough. We lived in a basement apartment in a tough neighborhood in Queens. Money was really tight and both my parents worked hard to make ends meet. I was old enough to understand our financial situation and rarely asked for anything unless my parents offered to buy me something, like toys. I remember my mother used to sew these red suspenders every night for $0.03 each and she would do thousands at a time. We grew up speaking English so that was not a problem but my accent was. Other kids made fun of me occasionally, but it only bothered me a little. I was kind of a loner because I was shy and an outsider. It was also really cold in the winter, but snow was so exciting since we had never experienced that.

A vivid memory of those early days was the first time I walked down 5th Avenue. It was a blustery night and I only had a sweater on. As we walked I felt the cold wind on my face and saw how glittery the sidewalk was and thought, “What a rich country America is, they have sidewalks made of diamonds even!”. And, of course, there were the huge towering buildings above me, that my dad had promised.

I was 9 years old when I first rode the subway on my own. My parents simply told me to keep my eyes open and not to go with any strangers that might ask me to follow them. Other than that they said, I knew where I had to go and it would be easy, it was time for me to grow up and be independent! I rode the subway throughout NYC on my own or with my little brother ever since.

I remember the first time I had Chinese food, a hot dog, a slice of NY Pizza and wow did they taste great, even better than the “boring” curry we’d have at home! My brother and I really liked American music of the ’80s like Michael Jackson, the Police, the Bangles, etc. and I hated it when my parents played Indian music because it was un-American in my mind but my parents insisted that we had to hold on to our culture and not just immerse ourselves into all of American culture. They very much disapproved of young American women’s dress sense and of men wearing earrings and sporting tattoos. The world felt new, exciting, and dangerous.

TK: After deciding to move to the Bay Area, I was excited about the warmer climate and its beautiful geography but didn’t expect it to be all that different. After all, we shared the same language, ate the same foods, and listened to the same music. When I arrived in Palo Alto, I was struck by how small the “village” was in contrast to bustling London and how similar everyone seemed in the way they dressed, talked, and shared interests despite the fact that they came from many different backgrounds. In contrast, people in London tend to retain their identities of their home culture and were part of close knit ethnic communities. London seemed to comprise more of a tapestry of cultures whereas America is a melting pot where people adapt to a common local culture.

The lifestyle here is very different. People live to work here, it appears to be at the center of their lives and forms their identities. In London, people work to live, counting down the days till they get out of the office to be with their friends and family. A job is generally a job, and life is rich and full of people you care about. The two didn’t blend a whole lot and were fairly distinct. I was shocked when so many people I met here didn’t even use up all their vacation days! That is unheard of in London, and we get so many more days there – we start at four weeks and usually build up to six to eight weeks, in addition to public holidays.

What were some of the differences between America and London/Tanzania that struck you?

TK: I’ve noticed that the economic discrepancy is larger here than in London. The concentration of the homeless in (San Francisco’s) Tenderloin neighborhood (many of whom seemed to have mental problems) would be taken care of, if they were in London. It was shocking to realize that these people who were ill were left to fend for themselves. The notion that everyone is responsible for their own healthcare seemed ridiculous (its provided for with a wage tax in the UK). However, the health clinics in the Bay Area were so nice compared to the facilities in London along with the attention and respect doctors give you here in answering questions and explaining things to the patient. They even provide the information and choice of therapy to you, which I never experienced in the UK. And I had a lot of experience accompanying sick relatives to the doctors!

In general people are friendlier to strangers here and the notion of customer service just doesn’t exist in London generally. However, if you’re a regular, then you get treated with a lot more love and freebies! So the bar is higher but, when you cross it, people seem more generous in London and much less transactional in their relationships.

Do you still have family in your home country? Is there anything you miss?

AK: Yes, I do have some cousins there and I’ve been back three times since we moved here. The first time was in 1985 (three years after moving to New York), which I can’t remember anything about except getting on the plane and listening to Tears for Fears on the headset the whole way! I went back in 2000 and 2003 for weddings and ended up climbing Kilimanjaro in 2003.

As an adult, I miss the sense of safety that seemed to envelope children in my childhood. Running into people you knew all day long just made a place a community and I’ve never experienced that sense of belonging or familiarity except in college, and then for a couple years in Palo Alto while working with Karen Leshner (the venue host for our event and Tapestry Suppers board member). The city of Dar, being a small city with a tight knit community meant that there were always eyes watching over kids when their parents weren’t. This was a bad thing if you were up to no good, because it would be reported to your parents or, just as commonly, being disciplined by the neighbor or relative who witnessed you doing something you shouldn’t have been doing! It’s probably no longer the case there today, just as it isn’t here in the US.

TK: My mom and sister live in London and we usually visit once a year. I miss the social aspects of living there. Friendships seem more formal here, where long time friends will still expect that you give them notice before showing up at their door. In London, its totally fine to stop by unannounced if you’re in the neighborhood. People are also not as planned out or structured, leaving a lot of time for spontaneous visits or adventures. Kids’ naps and meals, for example, are not the center of every parent’s life! Kids are treated as adaptable beings, just like adults, and are not as coddled, being assigned real chores and responsibilities and given independence early on. It’s totally normal to see 10 year olds walking to school unaccompanied by their parents or riding on a bus. I was making rotis and rice every day after school for our family dinner and so did my friends!

Any other anecdotes?

AK: I’ll just say that my dad was very optimistic about everyone’s ability to make something of themselves in America. He truly was here to be a part of the American dream. He emphasized to me that if I worked hard and studied hard that I could be whatever I wanted to be. And if I didn’t, well then I’d end up being a garbage man or working at McDonald’s! And for whatever reason, that was not what I wanted to be, so I worked hard. But that sense of self-reliance, of making your own way in life, has stayed with me throughout the years. Over time I also came to understand that just as important as my education were the people that took an interest in me along the way, supported me and took me under their wing or simply gave me an opportunity to prove myself. Whether it was teachers who saw potential and zeal or later in my career, people who vouched for me or took a shot with me. I very much think that Karen was one such person, and I’ve always been very appreciative of that.

Can you tell us a bit about the menu you’ve planned for this lunch?

TK: We are cooking family recipes that have special memories associated for us. These dishes connect our families today with the places and communities that they’ve come from over many generations. For me, planning a large feast like this would generally be for an iftar party we’d host during Ramadan. We’ll start everyone off with a date, which echoes the Muslim practice of breaking their daily fasts in the holy month of Ramadan, so I thought it would be appropriate to kick off our feast with like this as it is an important part of our background.

We’re serving puff pastries as appetizers (sometimes called Sambusa in Swahili). This is originally an Indian dish (Samosas) that East Africans have adopted as their own. It’s a truly international amalgam between Indian, East African, and Middle Eastern cultures. Even the local language, Swahili, is a combination of the original Bantu and Arabic spoken by traders from the Middle East.

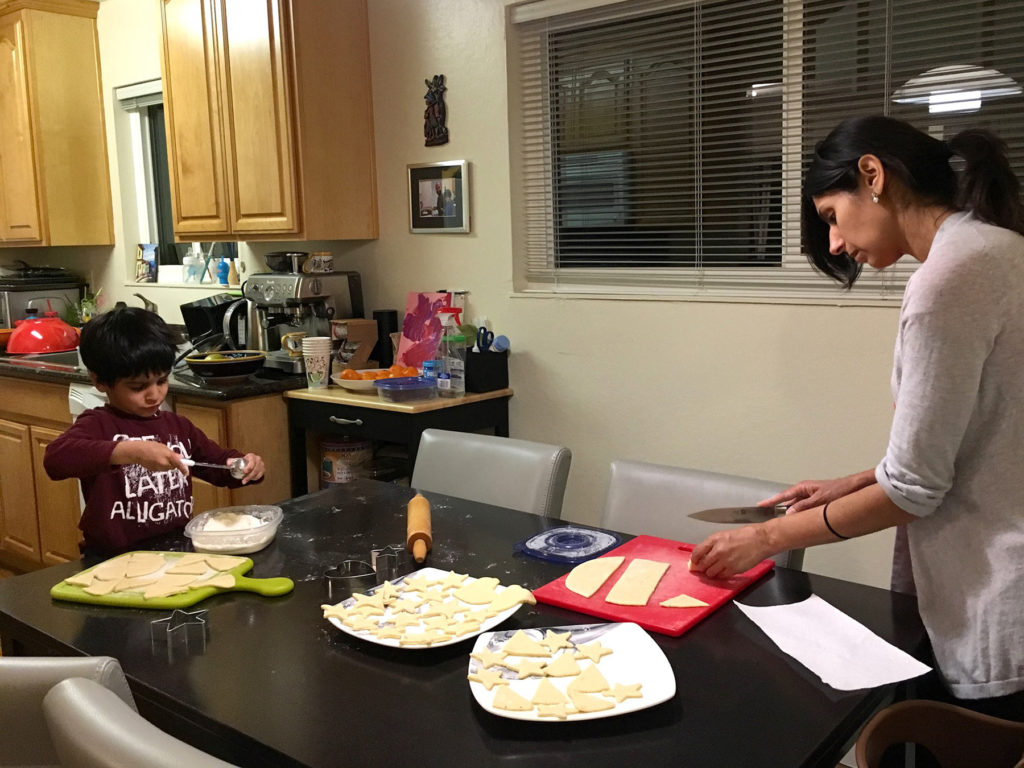

My great-grandmother taught my mother her Sambusa recipe in their hut in Nairobi. I would take them to school for lunch as there was no way I would eat bangers and mash! Making those pastries together was something that we bonded over. I’d be standing on a stool at the kitchen counter, with my own mini-rolling pin rolling out the home-made puff pastry sheets as my mum filled them. This tradition continues today since my 4-year old won’t touch anything easy to make for lunch, like a grilled cheese sandwich, and so he goes to school with these Sambusas in his lunchbox!

The cassava fries (called Mogo in Swahili) are a staple in East Africa, and bring back memories from my visits to the beach in Dar-es-Salaam, as they do for my mum when she was young. We’d go in the afternoon when it was hot outside and hang out until the evening, when local food vendors showed up in the evening with their grills filled with grilled kabobs, corn, and mogo chips.

Growing up in the culture that we did, our parents continued to cook the foods they grew up with as Muslim Indians in East Africa. These are foods that blend classic indian curries with local traditions and ingredients.

For the main course, we’re serving Kuku Paka (Chicken coconut curry), which is a Swahili name for the dish that melds grilled chicken in a coconut-based Indian curry.

Finally, the Falooda we’re serving for dessert is another Ramadan tradition that usually is served after the date with a Sambusa, which is then usually followed by group prayers before really taking on the main meal. Since we are not fasting today, nor partaking in praying before the big feast, we thought it would be better served as a cool dessert to help settle some of the more sensitive palates after our meal.